WASHINGTON (July 14, 2020) — The National Transportation Safety Board determined during a public board meeting held Tuesday that Atlas Air flight 3591 crashed in Trinity Bay, Texas, because of the first officer’s inappropriate response to an inadvertent activation of the airplane’s go-around mode, resulting in his spatial disorientation that led him to place the airplane in a steep descent from which the crew did not recover.

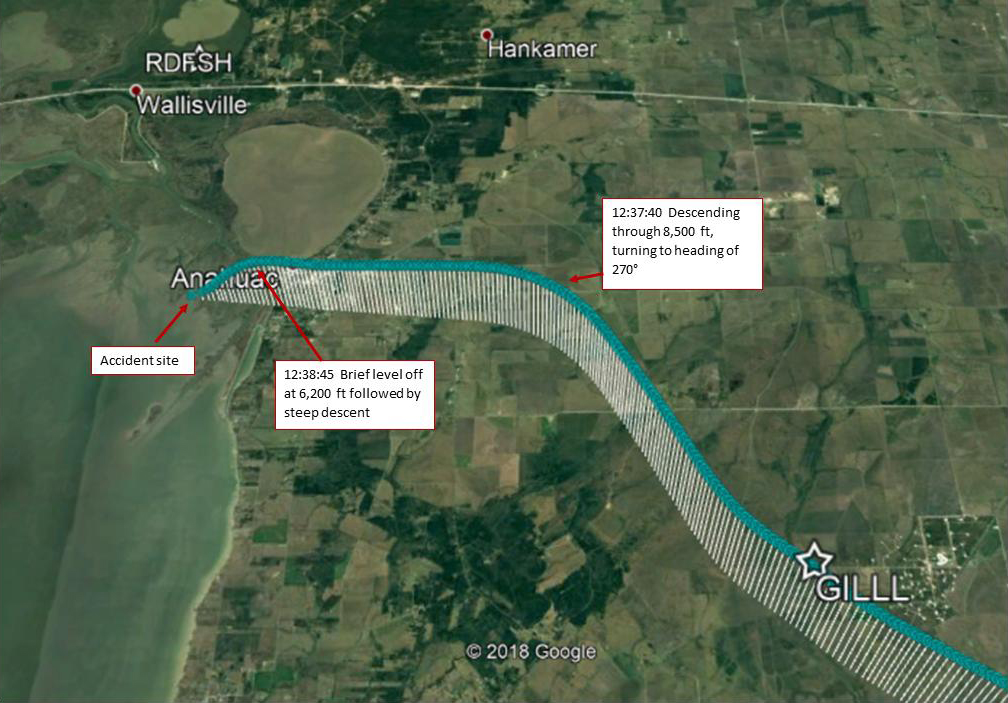

The accident happened Feb. 23, 2019, when the Atlas Air Boeing 767 cargo jet entered a rapid descent from about 6,000 feet and impacted a marshy bay about 40 miles from Houston’s George Bush Intercontinental Airport. The captain, first officer and a non-revenue, jumpseat pilot, died in the crash. The airplane – which was carrying cargo from Miami to Houston for Amazon.com Services LLC., and the US Postal Service – was destroyed. The first officer was the pilot flying the airplane at the time of the accident.

The NTSB also determined the captain’s failure to adequately monitor the airplane’s flightpath and to assume positive control of the airplane to effectively intervene contributed to the crash. Also cited as a contributing factor is the aviation industry’s selection and performance measurement practices that failed to address the first officer’s aptitude related deficiencies and maladaptive stress response.

The NTSB concluded the first officer likely experienced a pitch-up somatogravic illusion – a specific kind of spatial disorientation in which forward acceleration is misinterpreted as the airplane pitching up – as the airplane accelerated due to the inadvertent activation of the go-around mode, which prompted the first officer to push forward on the elevator control column. The first officer subsequently believed the airplane was stalling and continued to push the control column forward, exacerbating the airplane’s dive. However, no cues consistent with an aerodynamic stall —such as stick shaker activation, stall warning annunciations, nose-high pitch indications or low airspeed indications—were present. Additionally, the NTSB’s airplane performance study found the airplane’s airspeed and angle of attack were not consistent with having been at or near a nose-high stalled condition. The first officer’s response was contrary to standard procedures and training for responding to a stall.

(Graphic depicting of the descent of Atlas Air flight 3591 before final impact on Feb. 23, 2019. NTSB Graphic)

The NTSB concluded that while the captain, as the pilot monitoring, was setting up the approach to Houston and communicating with air traffic control, his attention was diverted from monitoring the airplane’s state and verifying that the flight was proceeding as planned. This delayed his recognition of, and his response to, the first officer’s unexpected actions that placed the plane in a dive. Investigators also concluded the captain’s failure to command a positive transfer of control of the airplane as soon as he attempted to intervene on the controls enabled the first officer to continue to force the airplane into a steepening dive.

While the first officer took deliberate actions to conceal his history of performance deficiencies, Atlas’ reliance on designated agents to review pilot background records and to flag significant concerns was inappropriate and resulted in the company’s failure to evaluate the first officer’s unsuccessful attempt to upgrade to captain at his previous employer. Additionally, the NTSB found that had the FAA met the deadline and complied with the requirements for implementing the pilot records database as stated in Section 203 of the Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administration Extension Act of 2010, the pilot records database would have provided hiring employers relevant information about the first officer’s employment history and long history of training performance deficiencies.

“The first officer in this accident deliberately concealed his history of performance deficiencies, which limited Atlas Air’s ability to fully evaluate his aptitude and competency as a pilot,” said NTSB Chairman Robert Sumwalt. “Therefore, today we are recommending that the pilot records database include all background information necessary for a complete evaluation of a pilot’s competency and proficiency.”

As a result of its investigation, the NTSB issued six new safety recommendations to the Federal Aviation Administration and reiterated six previously issued safety recommendations to the FAA, four of which the NTSB also classified “Open—Unacceptable Response.” The new safety recommendations issued Tuesday address flight crew performance, industry pilot hiring process deficiencies, and adaptations of automatic ground collision avoidance system technology. Two of the reiterated safety recommendations seek the installation of cockpit imaging recorders on all aircraft operated under Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 121 or 135 required to have cockpit voice and flight data recorders. The four recommendations that were reiterated and classified address maintaining accurate pilot training records.

An abstract of the final report, which includes the findings, probable cause, and all safety recommendations, is available at https://go.usa.gov/xfbcb.

Links to the accident docket and other publicly released information about this investigation are available at https://go.usa.gov/xfTNs.

The final report for the investigation of the accident is expected to post to the NTSB website in the next few weeks.

To report an incident/accident or if you are a public safety agency, please call 1-844-373-9922 or 202-314-6290 to speak to a Watch Officer at the NTSB Response Operations Center (ROC) in Washington, DC (24/7).